|

|||||||||||||

|

Criminal Heroes and Secret Societies By Punkerslut

Criminal Culture is the culture of those who break the law and want to change society. In participating in this underground society, we are not entirely revolutionaries and we are not entirely criminal. We are something very different from the teeming mass of thieves, drug dealers, and pimps found throughout every city; and we are also something very different from the smooth talkers, the self-admirers, and the ego-obsessed politicians of Liberalism, Socialism, or Progressivism. We are the Criminal Culture; we are Illegalists. The law separates us from what we need presently and the world deserves in the future. We act out of self-interest in the moment as Individualist Criminals, and out of the possibilities of the future as Collectivist Revolutionaries. The ideals give direction to the criminal behavior, and in a mutual way, being a criminal gives color and persona to our revolutionary thinking. An endless amount of steam or ice would never never turn to water; but if you mix both of them, you get something drinkable and nourishing. Participants in Criminal Culture become unique from both revolutionaries and criminals. We have only one unbreakable rule: we only fight exploiters, and only do so in a way that benefits the exploited. It is easiest to believe this when you know our story more closely.

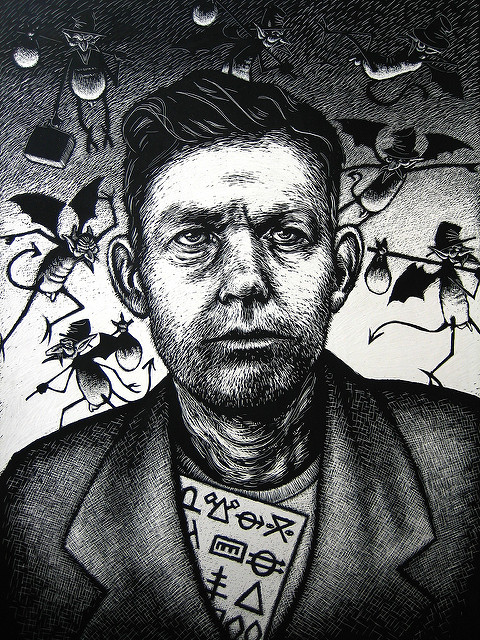

In Catalonia in the year 1936, Anarchists created the first, modern Anarchist society with millions of inhabitants. It was an egalitarian society: workers in charge of their workplace, neighbors in charge of their neighborhoods, and families in charge of their homes. And such a wondrous achievement could hardly be achieved without crime. Juan García Oliver was one of the most influential Anarchists in Spain at this time, and he remembers his introduction to the concept of solidarity... ...at the age of 7, he and a bunch of friends were chased away from a hot air vent outside a textile mill in Reus (near Barcelona). Later that night they returned and broke all the windows of the watchman's hut...and they were never chased away again. [*1] The Anarchists of Spain inspired a sense of righteousness in the duty toward crime. The entire people listened, as we can tell from the written record... ...low-paid workers presumably had few problems in justifying the appropriation of the property of their employers as a 'perk' or as compensation for poor pay; similarly, the frequent armed robberies directed at tax and rent collectors were unlikely to concern workers. Moreover, since the working class was essentially a propertyless class, these illegal practices rarely impacted upon other workers. [*2] When the Great Depression hit Spain in the 1930's, people stole groceries from the market and explained their actions by saying "because of the recession ," they ate at restaurants and bars without paying because of "the right to life," and they stole crops from farmers' lands because "the land is for everyone!" [*3] The Spanish, Anarchist periodical Tierra y Libertad ("Land and Liberty") suggested that "robbery does not exist as a 'crime'...It is one of the complements of life..." and they went so far as to say that illegality is "anarchist and revolutionary." [*4] Underneath this attitude was a deep and compassionate feeling for the masses. The governments of the world then taught that criminals are deformed humans by birth, with scientists like the popular Lombroso suggesting biological and ethnic causes of crime, and other so-called "Phrenologists" saying they can tell if someone is a criminal by measuring their skull. The Anarchist newspaper, Solidaridad Obrera ("Worker Solidarity"), had a different philosophy: "there is no such thing as 'good' and 'bad' people, only people who are "good" and 'bad' at different times...." [*5] It would be impossible to talk about criminal culture in Spain without mentioning the name Buenaventura Durruti . He was drafted into the Army to put down a rebellion in Morroco, but he walked up to his commanding officer and said, "[King] Alfonso XIII is going to have one less soldier and one more revolutionary..." before deserting. While the police were looking for this deserter, local miners decided to give Durruti shelter. In town, there had just been a miners' strike, and the brutality of the authorities resulted in enough hostility to the police, that the people were accepting fugitive Anarchists with open and loving arms. [*6] Durruti and his comrades were members of the CNT-FAI, the multi-million member Anarchist-Syndicalist trade union. They wanted to rob some of the Madrid banks, and they were able to acquire arms from other workers, at "a time when a gun was the best membership card." With these humble but honest resources, Durruti and a few others were able to rob a transport from the Bank of Bilbao, netting 300,000 pesetas: the sum was divided between revolutionary groups in Bilbao and Zaragoza. [*7] Then Durruti needed money to live in exile, so he and a few others, calling themselves Los Solidarios , robbed a transport from Barcelona City Hall, only a block away from the bank, netting 100,000 pesetas. [*8] In a third bank robbery, the bank manager presumably knew who Durruti was, walked up to him, and slapped him in the face; he began cooperating after receiving a non-fatal shoulder wound from the bank robber. [*9] Some of this money went to the French Anarcho-Communist Union (ACU), which had a storefront for its bookstore and "In the back, there was a room used for everything: storage, editing, running the newspaper, and ACU administration." When Durruti and friends were visiting, he found a campaign to stop the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, two Americans sentenced to death largely based on their Italian-immigrant origins. [*10] Working with his French comrades, Durruti and others with him, including Francisco Ascaso, smuggled themselves aboard a ship bound for Cuba, in order to escape their captors. They took up work at a sugar cane plantation in Santa Clara, and they were soon engulfed in a labor strike, where the managers "seized the three supposed ringleaders and dragged them off to the closest rural police post..." and when the union organizers were brought back, they "had been beaten so badly that they dropped lifelessly at their comrades' feet." That night -- Ascaso and Durruti gained access to the mansion of the landlord, finding him in his sleep, and cutting his throat. They only left a note reading "The Justice of Los Errantes (the Wanderers)". The story turned into a wild rumor, with the vast majority believing that Durruti and Ascaso were killing dozens of landlords and capitalists, and soon, copycat crimes spread across all of Cuba, engulfing plantations known for particularly brutal, exploitive, and cruel managers. [*11] Durruti and Ascaso left Cuba for Mexico at their earliest chance. Here they were sheltered by a group of activists trying to establish a Rationalist School in the style of Francisco Ferrer, where there would be no sexism, no racism, no classism, and no authority. Before leaving Mexico, Durruti and Ascaso robbed the La Carolina factory, delivering the sum to the militants at the Rationalist School. They knew that these men were the alleged robbers, because the amount of money donated corresponded to what the factory had reported stolen, down to the last centavo. [*12] They kept moving southward, Durruti, the Ascaso brothers, Gregorio Jover, and Gregorio Martínez, the last man wanted for creative uses of dynamite in Spain when police tried to break up strikes. In Chile, this group robbed a bank for nearly 50,000 Chilean pesos, firing warning shots to get bank guards who were clinging to the getaway vehicle to let go. The entirety of these funds were directed to the underground struggle against Primo de Rivera, the Spanish dictator who seized control of the government by force, shut down all opposition (including the unions, of course), and enforced a brutal martial law throughout all of Spain in 1923. [*13] Still on the move, in Buenos Aires, Durruti and two others tried to hold up a bank, but had arrived late in the day, when no keys to the safe were available on the premises. [*14] Shortly later, in Argentina, they robbed a branch of the Bank of Argentina. This time, their plans did not focus on getting access to the vault, and they merely collected money from the counter registers at a busy period. They make away with around 65,000 Argentinian pesos. [*15] It was just another addition to the sum donated to the cause of the strugglers. When a beggar once asked Durruti for money, he responded by handing him a gun and responding, "Take it! Go to a bank if you want money!" [*16] After his return to Spain, he stopped being a heroic bank robber -- he organized his own column of fighting soldiers who fought the Fascists while attempting to realize Anarchist-Communism. He was once told, "You will be sitting on a pile of ruins if you are victorious." He responded with... "We have always lived in slums and holes in the wall. We will know how to accomodate ourselves for a time. For you must not forget, we can also build. It is we who built those palaces and cities here in Spain and America and everywhere. We, the workers, can build others to take their place. And better ones. We are not in the least afraid of ruins. We are going to inherit the earth." [*17] Durruti was a well-respected revolutionary, but he was also a devoted member of the underground, criminal culture. In the United States and throughout all of Europe, liberals and conservatives sold guns, trucks, and oil to the Nazis; Durruti and the Spanish Anarchists committed crimes to resist them. And in the end, after the US-UK-USSR alliance was victorious in the Second World War, the governments of the West spit on Durruti's achievements, "some of our so called comrades attempted to defame our conduct in this matter -- calling us robbers, bandits, criminals in exactly the same way as our fascist enemies." [*18] In Germany, Hitler lost, but in Spain, Hitler was victorious, and these same Western governments consented to the Spanish concentration camp system -- the camps that incinerated Liberals, Poles, and Jews were abolished, but those that incinerated Anarchists, Socialists, and Catalans kept going. To quote the Spanish CNT-FAI militant and Anarchist, Miguel García... "When we lost the war, those who fought on became the Resistance. But, to the world, the Resistance had become criminals, for [Hitler's Ally] Franco made the laws, even if, when dealing with political opponents, he chose to break the laws established by the constitution; and the world still regards us as criminals. When we are imprisoned, liberals are not interested, for we are 'terrorists'. They will defend the prisoners of conscience, for they are innocent; they have suffered from tyranny, but not resisted it." [*19] Durruti's full biography was eventually funded with a money-counterfeiting operation France, [*20] and its author was blacklisted for his Anarchist associations, although a local union was able to get him a job. [*21] And Durruti was not the only one. César Saborit Carreiero was another Spanish hero of the criminal movement. His favorite targets were members of the Spanish, Catholic mafia; when he found their goons taking protection money in his neighborhood, he disarmed them (sometimes at the price of their lives), and turned over their proceeds to the local unions. Another avenue for making money was in smuggling Jews and Liberals over the Pyrenees borders and away from Hitler's camps; if they were poor, he charged nothing, but if they were rich, he charged excessively. [*22]

In the 1970's, a series of bank robberies in Spain broke out like fire. It was the work of the Iberian Movement of Liberation (MIL), and its organizer, Salvador Puig Antich, would be the last person executed by the midevil method of garroting (machine strangulation) in Spain. The MIL carried out lucrative activities: raiding a printing press for materials to be used in Anarchist propaganda with an estimated value of 76,000 francs in 1972, the 24 million pesetas stolen from Barcelona banks in 1973, and firing guns just outside the offices of the "Social-Political Activities Brigade" of the Spanish police department. [*23] The Catalan organizer of the MIL, Antich, signed all of his letters with "Salud and Anarchy," the organization published dozens of tracts on Anarchist-Communism, and Antich's ultimate goal was to "combine Catalan nationalism with Anarchism. [I know this because] a cousin of mine was in jail with Puig Antich the weeks before he was garrotted. Puig Antich taught him [the] Catalan [language] there... " [*24] The organization focused on "armed agitation," which meant "shunning attacks against the person," so they focused on robbing from banks and stealing printing equipment, viewing themselves merely as "a support group for workers' movement struggles and its activities..." [*25] As Anarchist bank robbers, the MIL left leaflets behind at the crime scenes, one of which read: "This expropriation, together with the preceding ones, is designed to support the proletariat's fight against the bourgeioise and the capitalist state..." [*26] After a bank robbery near the French border in September, 1973, 12 MIL members were arrested, 3 of them facing the death penalty. But they didn't want to become heroes , "they did not aspire to capture the imagination, but merely provided the material means for action in a country where a large quantity of them is often needed." [*27] The MIL was not the only Illegalist organization operating during the 1970's in Spain. The Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) is a Marxist, revolutionary group operatingthrough kidnappings, shootings, and bombings, and, like the Catalans, they are a minority European group: the Basques. In 1973, they carried out Operation Ogre, the assassination of Luis Carrero Blanco -- the next in line for the Hitler's hand-picked Spanish dynasty. The events following Spanish history after this event are known as the Spanish Transition to Democracy, and the group that organized it, the ETA, isn't even Spanish, but Basque; once again, the most significant events in so-called Spanish history are not affected by Spanish people, but by minority peoples who have long known been oppressed for their non-Spanish culture. The ETA also worked with illegal union organizations, smuggling, and every bit and parcel of the Illegalist underworld. Why do they matter? They freed Spain from the Nazis, using crime and criminalism, when the combined forces of the UK, the US, and the USSR couldn't make them budge from their Iberian peninsula. For this feat of Democracy, the United States government has declared the ETA to be a terrorist organization, [*28] while at the exact same time, the United States government has declared the resulting government from ETA's actions to be an ally of the United States. [*29] The United States Department of State does not listen to logic; but people like them have been forced to listen to the sound of dynamite. If it is Democracy that is at stake, what costs could make us falter? The 1930's burned out and the 1970's faded away, but Criminalism never ceased in the Spanish countries. In the early 2000's, people in Barcelona, Catalonia, began to steal from multi-national corporations by directly lifting merchandise at stores and removing it, only declaring "Yo Mango!" ("I Steal!") One of the organizations involved "provides free workshops on how to defeat security systems through orchestrated teamwork that on one occasion, to mark the Argentinian riots of December 2001, took the form of a choreographed dance session." [*30] Dances and dynamite, shoplifting and smuggling. Spain was known the world over for its over-reaching empire and slave-trading network; it is time that the other side of the reality is exposed, and we see a truly beautiful world underneath the misery of oppression and exploitation.

I open the door facing me in Catalonia, walk through, and emerge on the other side to "all of Europe." Throughout the Feudal era in Europe and parts of Russia, peasants developed their most-used tool against oppression: the conspiracy of silence. If one peasant hacks off the head of their lord, even if the act was witnessed by a thousand other peasants, they only replied to investigators with "muttering and grumbling", with an excessive use of "euphemisms and metaphors," to make their meaning totally alien. Similar tactics proved especially useful during the Witch Hunts, where female peasants were persecuted extremely harshly, and likewise, were accepted as full-fledged members of the underground, criminal society. [*31] The "conspiracy of silence" was more than just a non-cooperation tactic with authorities. When private production of alcohol was outlawed, the criminal societies taught it; when harvesting fallen branches and wood in a public, common area was prohibited, the criminal societies showed how to steal it; when men demanded a Sexist domination of the world, criminal societies introduced the all-women's collective dwelling. [*32] These activities, along with the conspiracy of silence, were what peasants lived through and endured throughout all of Europe for the past half millenia. Poland had its own criminal, peasant societies, and they would steal grain from barns, fish from ponds, and wood from orchards. These actions led to a criminal culture: "As peasants stole commodities they would often tell stories about their daring feats." [*33] And when these tactics failed, the Polish peasant fell back on their own wits: they moved and relocated property markings or extended their fencing near the landlord, as a means of increasing their own landholdings. [*34] The city of Dubrovnik (now Ragusa ) in Southeast Europe, on the Dalmatian Coast, has the motto, "It is a bad deal to sell your liberty for all the world's gold." This is perhaps fitting, because the city itself was founded by runaway slaves, and once they had established a fugitive's fortress, "its merchants and literary men played a leading role in the economic and cultural life of the peninsula." [*35] It still exists as a completely independent power, from its humble beginnings in the 1300's to the present day. The Greek peasants who fought against their governments and landlords were known as Klephts , and these rebels existed for from the 1400's until the 1800's. One song originally written by a Klepht describes the perfect coffin: "wide, long, roomy enough for two; to stand erect, fight, take cover, reload; and on my right side, leave a window; so that the birds may fly in and out, the nightgales of Spring..." [*36] Their name, Klephts, has the same etymological origin as the word "Kleptomia," the English word to describe habitual stealing. In Serbia, these rebellious peasants were called Haiduks, and their hero was Marko Kraljevich, who was "a fabulous drinker", and allegedly, so was his horse. In one story, when his mother ordered him to stop being a bandit and to try to settle down as a farmer, he accidentally ploughed land belonging to the Tsar of Russia. He was interrogated by some janissaries, the local, corrupt police force. In this altercation, he beat them to death with his plough, carried off the bribes they had collected, and returned home, "Look, mother, what my plowing has won for you today!" [*37] East of Serbia, in Bulgaria, illegalists were called Haiduits, a dialectical variation of the Serbian Haiduk. These were bolder peasants who responded more strongly to exploitation and extortion of state-sanctioned employers ("chifliks"); they "abandoned their plots and took to the mountains or forests, where they led the perilous but free lives of outlaws." They robbed from the soldiers and tax collectors of the Ottoman Empire, "and sometimes the rich Christian oligarchs and the monks of the well-stocked monasteries, in preference to the poor peasants or the parish priests." They were known "not as ordinary brigands but rather as champions of the lowly and the downtrodden." [*38] Those were the ancient traditions of those living in the Balkans (that term of endearment for Southeast Europe). But these traditions continued into the modern era. The Greek revolutionist Adamantios Koraïs struggled to overthrow the Ottoman Empire that enslaved his people, and in so doing, he became a part of the underworld, where he "joined secret lodges, organized new ones, and wrote and distributed various revolutionary tracts." [*39] One of these criminal organizations was known as the Society of Friends ("Philike Hetairia") to disguise its activities from the authorities. If there is certain proof of its criminal origin, it is that almost virtually nothing is known about this secret society. And if there is certain proof of its good nature, it is that its revolutionary war against the Ottoman Empire was enough to free Greece from its clutches. [*40] When the Greeks realized that the Capitalist Nation-State was just as oppressive, the secret societies became active again: the carried out shootings and bombings of those representing the banking industries into the late 1800's. Dimitris Matsalis, one of the secret society members in Greece who was caught, gave this as his final confession, 1898... "What I did was for the sake of the idea. Nobody pushed me. I did it by myself. By killing them I didn't aim to the particular people, but I struck Capital. I am an anarchist, and anarchists are for violence.... the other socialists are ridiculous and nothing links me with those. They want to impose their ideas by persuasion, while I, as an anarchist, support terrorist violence." [*41] It would be difficult to write a history of Revolutionary Europe and to leave out France. Here, in 1848, when poverty became merciless, peasants reacted by making "attacks on grain shipments or market riots," and ideologically, these groups "took the form often of a challenge to the socio-economic power of the rich, of the richer landowners and the userers, or to the authority of the state as tax collector and forest guard." Throughout France, although most notably in Massif Central, a stone's throw from Catalonia, there was "an increasing hostility of the poor towards the rich as a group rather than towards individual rich men..." [*42] In a statistical analysis of the participants of these criminal French groups, it was determined that "a large proportion of those arrested were married men," and in Languedoc, just neighboring Massif Central, "it has been calculated that two-thirds of those deported after the coup were married and eight-ninths of these were fathers." [*43] According to state records, when these criminals were deeply interrogated by the torturers of the state, many of them had to confess... ...of their griefs against the [National, Parliamentary] Assembly, of their sadness at seeing the [Napoleonic] revolution stain itself with blood... of their misery, of their hunger, of the destitution of their children and their wives. [*44] Marius Jacob escaped from an insane asylum in Aix-en-Provence and quickly formed an illegalist band with other French comrades: they swore never to kill (except in self-defense), only to steal from the rich, never to steal from the poor, [*45] and to "give the bulk of their sensational hauls to the Anarchist movement." [*46] Francois-Claudius Ravachol, or merely Ravachol , is another French comrade, who used counterfeiting and forcible expropriation to fund the purchase of dynamite so he could blow up the homes of judges and politicians. [*47] There is also Jules Bonnot, the organizer of the so-called Bonnot gang, which robbed from wealthy exploiters of the poor in the years of 1911 to 1912. Its leader has been described with every term imaginable: "a charlatan, a dandy, a sociopath, a criminal masquerading as an anarchist, or vice versa." [*48] In Italy, during World War 2, the principle source of food for the population was the Black Market, largely due to the absence of any Humanitarian-feature of the US-UK-USSR Alliance here. One black marketer smuggling foods into the country was assaulted by a police officer in an attempted arrest, freeing himself only by shooting his captor. His name was Salvatore Giuliano, and he soon organized a band of Italian brigands to make sure that every family in Italy could sit down to enough food to satisfy their appetites. But he was not an Anarchist; he became obsessed with the Sicilian Nationalist movement, and sided with the Sicilian mafia in a dispute against peasants, leading to his downfall. [*49] Moving to more current times, on September 19, 1994, a group of Anarchists were arrested in Italy for the robbery of the rural bank of Rovereto in Seravalle. After being caught and interviewed, one Anarchist had this to say: "I don't think that there’s anything exceptional about anarchists deciding to take back some of what has been stolen from us all -- we have to face the problem of survival like all the other dispossessed..." [*50] At their trial, activists climbed the courthouse and drew a circled A with lipstick, and outside their prison, activists set off fireworks and paint bombs. [*51] Italy is also home to the Brigate Rosse ("Red Brigades"), a Marxist organization like the ETA that had carried out bombings, kidnappings, bank robberies, and all sorts of sabotage. [*52] When enough members of this organization formed a sizable population in the prisons, they developed an internal culture of political prisoners. They were known for calling every police officer they came into contact with stronzo ("shit"), and if they suffered any retaliation, the members of the Red Brigades would riot in excess. It became an earned right, and no mobster, gang member, or petty pickpocket could even attempt to use it for themselves. [*53] This distinction in prisons between normal population and political prisoner population will be found elsewhere. Bank robberies are quite high profile, though. Many Italians in the modern era engage in a practice known as Proletarian Shopping. This may be as direct as shoplifting, or it may be socially organized such as a demonstration or a sit-in of a shop by consumers to reduce prices. The simple premise was that "proletarians requiring or yearning for goods will steal them." [*54] In Walsall, Great Britain, in the late 1800's, a group of Anarchists was arrested for buying the parts and possesing the plans to build a bomb to be used against the Russian Tsar. Naturally, the case involved a good deal of forgery by the police, but what could not be forged was that many of the accused had come together because they "had occassionally spoken at unemployed meetings," and they mutually assisted each other, having the habit to "always give liberally to any whose only claim was their need." [*55] Moving North of Walsall, you come to Sheffield, England, where Dr. John Creaghe and his supporters formed the Sheffield Group of Anarchist Communists. For Creaghe, it is the poverty of Capitalism that forced workers "to retake from the rich a part of what they have stolen." And he urged the criminals onward, "continue...your resistance to this vile thing called property!" Their journal had ads enlisting bank robbers in the service of the made-up, corporate name "The Wealth Restitution and Bank Exploration Trust Co." He lectured that real revolutionaries are bandits who "live off of the enemy." [*56] When bailiffs in town tried to seize the goods of a poor man for debt, he chased them out of his house with a kitchen poker, and the children of Sheffield came up with the rhyme... "Hurrah!; for the kettle, the club, and the poker Good medicine always for landlord and broker Surely 'tis better to find yourself clobber Before paying rent to a rascally robber." [*57] "He was a good outlaw, and did poor men much good," this how Robin Hood, who "stole from the rich and gave to the poor," is described in the conclusion to the first book published about him, in the year 1500. [*58] Between around 1250 and 1300, the name "Robin Hood" could be found on the dockets of numerous English judges; in a sense, it was a collective identity more than an individual one. [*59] Such a quiet, early beginning for all of this criminalism and illegalism. Go forward by almost a thousand years and you have the present times. The Chaos Computer Club is the largest organization of computer hackers in all of Europe, with more than 5,000 members. [*60] Its devotion is to "Human Rights and Democracy," but readings of its material will find provocative discussions on issues of piracy, sabotage, hacking culture, and hacking activism. A similar culture can be found in today's ThePirateBay.org (AKA: thepiratebay.se), where pirates and hackers regularly mock the state's concept of Human Rights while putting all intellectual property (movies, music, books, etc.) into a form freely accessible by the world commune. [*61] ThePirateBay, working in Sweden, has worked closely with the Piratbyrån ("The Pirate's Bureau") and Piratpartiet ("The Pirate Party") in furthering its objectives. One of the Chaos Computer Club members, Karl Koch, divided his time among a number of activities: for instance, he sold manufactured data about the US military to the KGB (the CIA of the USSR). He used this money to fund his numerous drug habits (cocaine and cannabis), but he had also hacked into the computers at the nuclear power plant in Chernobyl, Ukraine. The world would not listen refused to his listen to his warnings, and while he was hacking, the uranium components of the nuclear plant went critical -- many died and the entire city has since remained off-limits to all human life. After embarassing the CIA, the KGB, and every single Physicist in the world, Karl Koch's remains were found in a forest; it was determined that, while alive, he was burned to death by unknown assailants. A few suggest that he committed suicide. [*62]

The United States

Standing with my tip toes somewhere between Glasgow and Edinburgh, I feel like my whole body lifts up and I find myself somewhere new. Then I open my eyes and I can say in a united voice with my fellow Americans, "Ah, America, home! I love the place I live in, but I hate the people in charge!" [*63] Here in my homeland, the history of criminal societies begins with the history of slavery. African slaves had brought many stories with them about "a relatively weak creature [who] succeeds in at least surviving in his competition with greater beasts, usually by trickery..." The most well-known of these characters was Br'er Rabbit, who was "often absurd, but he is also filled with life and keeps struggling against his situation." Not only did this creature steal in a heroic act of glory, but he also tried "to lay the blame on others or cheat his accomplices, so he can distribute the food to his own family or sweetheart." [*64] Slaves who ran away from their plantations found a way to sustain themselves through an underground, clandestine, slave-driven economy. With aid from former fellow slaves, these runaways were able to steal "cattle, hogs, sheep, livestock, rice, cotton, corn, whiskey, poultry, grains, meats, even baskets, brooms, and farm tools." [*65] This was the subsistence that kept them alive while they were on the run. The slaves "made a clear distinction between the legitimate 'taking' of property from [slave-owning] whites and the reprehensible 'stealing' from their fellow slaves." One of the common establishments in this underground economy was the Grog Shop, a place known for its working-class clientelle and cheap liquors... Grog shops were spaces where slaves could sell goods, alcohol could be purchased, and blacks and poor whites came into contact and formed relationships. These establishments were usually owned by non-slaveholding, poor whites, and when the slave masters or the state sent vigilante patrols to suppress them, class antagonisms arose. [*66] This underground society kept them alive and warm; and by night, they kept awake and toasty when they burned down the homes of particularly hated slave patrollers and slavers. Arson was "common because it was easy and at times struck not only the master's immediate property but surrounding lands as well." [*67] Criminal society can exist even during forms of oppression that are as cruel as slavery. The end of so-called "legal slavery" was not the end of America's criminal societies, though, especially since wage slavery continues. The recession of the 1890's brought appalling misery and poverty all throughout the United State, which led to: "mass demonstrations, social and political radicalism, strikes, and violence." [*68] In those times, "urban Americans experienced unprecedent levels of labor violence and social disorder." [*69] George Brown, the Anarchist cobbler from Philadelphia, put the criminal nature of these labor societies more clearly.... "These unions have never been legal. At first they were under the direct ban of the law, and were prosecuted as conspiracies, which they undoubtedly were. They grew in numbers and power, however, until they were, and are able to defy persecution, and so they have secured toleration. But they are not, even now, legal, and are not suppressed only because they cannot be..." [*70] When the people themselves could not revolt directly, they made up stories about how the great criminals were bandits fighting for the poor. They made up these romanticizations of Dick Turpin, a horse thief who was probably unjustly executed for petty theft, Jesse James, an ex-confederate soldier who continued to fight Union soldiers in between bank robberies, and John Dillinger, the Depression-era robber of banks and police stations. [*71] But none of these criminals gave back to the community or had any humanitarian feeling -- they were not illegalists, just temporary enemies of the state. But for those poor who believed in them, we see that those without a real criminal culture to connect with will make it up if they have to. Upton Sinclair, the writer of Anti-War, Socialist and Labor causes, such as the books the Jungle and There Will Be Blood , spent one afternoon relaxing outdoors with his friends. The group was dutifully arrested by the local sheriff for violating the state's "Blue Laws," which prohibit leisurely activities on Sunday, "God's day of rest." Perhaps he wasn't a real criminal before, but once he was behind those walls and bars, Upton Sinclair's soul reached new heights as he discovered Illegalism, telling us... "With those noises [in prison] sleep is impossible, and in the morning, realizing I was a criminal, I resorted to theft in order that my lines might become immortal. I stole a sheet of paper and a pencil...and I wrote my poem ['The Menagerie,' an Anti-Prison Poem.]." [*72] During the 1930's, American politicians and businessmen grew a close, personal relationship with Hitler and the German economy. On the other hand, the American working people grew a close relationship with Anti-Fascism, so much so that, a group of several thousand volunteered to fight Hitler in Spain in 1936. Like other fighting units, they had the legal right to requisition vehicles for military use, but it just so happens that they often stole a vehicle belonging to the leader of the Spanish Communist Party, and "were forced, amid many humorous exchanges, to give it back." [*73] Even with the beginning of legalization for American unions in the 1930's, it was not enough to make them lose their criminal roots. According to William M. Leiserson, who was heavily funded by Carnegie and the Capitalist class, "When strikers go into disputes with nonstrikers they do not always limit themselves to intellectual argumentation." But, to be fair, he elaborated: "there is abundant evidence of employers hiring professional strike-breakers and thugs to beat up men on picket lines and active strike leaders." Even when there is peace between the dominant factions, there are always the workers who "carried on a sort of guerrilla warfare against employers without thought of extortion." [*74] This violence of the American citizen against seemingly uncontrollable conditions was not limited to just the workers in the unions. The struggle for Civil Rights, when its legal avenues failed to "produce rapid or perceptible changes in the lives" of African Americans "encouraged the adoption of more militant rhetoric." Politicians reacted most often by condemning this movement, making onlookers believe that "violence would create more progress." [*75] The Black Panther Party is one such manifestation of this attitude, and likewise, bank robbery was a regularly used tactic in the generation of much-needed, organizing funds. [*76] Br'er Rabbit isn't just a folktale. But unlike our counterparts across the sea in Europe, Americans tend to be very individualistic. In some cases this individualism is expressed with the private nature of family-based communities or in others with boldness in expressing new ideas in politics, society, art, culture, or music. Americans simply don't need the mafia, unions, and militant Civil Rights parties to get involved in crime. Ordinary people love to commit personal crime, like "the truck driver earning extra dollars by transporting stolen goods." In 1970, such non-violent behavior is estimated to make up as much as 5% to 10% of the average American's income. [*77] If you move to much more modern times, you'll find that we still make heroes out of the same old criminals in the United States: "'Yellow Kid' Weil, America's master swindler; Ben Reitman's fictionalized hobo activist Boxcar Bertha; François Eugen Vidocq, accomplish thief and the first true detective; and James Carr, criminal prodigy of the Los Angeles ghetto and prison rebel." [*78] Our obsession with an American Robin Hood is endless. A very modern reading can be found in the fast food restaurant just down any city block in America... "Like virtually all my fellow workers, I liberated McDonaldland cookies by the boxful, volunteered to clean 'lots and lobbies' in order to talk to my firends, and accidentally cooked too many Quarter Pounders and apple pies near closing time, knowing full well that we could take home whatever was left over." [*79]

Russia

When I chose the United States as the next direction after Europe, I could have just as easily chosen Russia: Glasgow and Edinburgh will lift me up to America, but Kiev in the Ukraine and Prague in the Czech Republic can lift me up to Moscow and St. Petersburg. Like most of the world, Russia has its criminal societies, too. Much of this history revolves around the history of the Russian Empire. Roman Dyboski was a Polish soldier imprisoned by the Germans and then by the Bolshevik Russians during World War 1. He was also a professor of philosophy and history, who spent his many years inside a concentration camp struggling to get his inmates to put together a play with him. When he put down his final words of gratitude in one published piece, they came out like this... "I cherish a lively, grateful, and exceedingly friendly feeling for a certain class of outcasts from society with whom I associated for some time. By this I mean various ex-convicts." [*80] The Russian Civil War was a struggle between two dominant forces, White Monarchists and Red Communists, but before it crystalized to this form, it was very uncertain what direction will lead to the future. When the Monarchist leader Kolchak was defeated, all White Monarchist troops retreated, and when they ran out of fuel, they got out of their trains and usually made a fatal march back to Berlin. Describing the scene of trains... "Immobilized for good and buried in the snow, they streteched almost uninterruptedly for miles on end. Some of them served as fortresses for armed bands of robbers or as hideouts for escaping criminals or political fugitives -- the involuntary vagrants of those days..." [*81] Durruti hid out in schools and miners' homes, American slaves hid out in grog shops and the swamps, Robin Hood hid out in the forest and its villages, and the Russian criminal society? They occassionally hid out in abandoned, military-fitted trains. One such particular society was organized by Alexander Antonov, who started out in such trains as this, with "odd bands of deserters from the Red Army, dispossessed peasants and other people 'on the run' for a variety of reasons." But before long, they gained in strength, "began a campaign of murdering Bolshevik and Soviet officials, raiding village soviets and court rooms (burning documents, like French peasants)...", and soon became known as the Tambov Rebellion. [*82] Far from the countryside, far from the Balkan Steppes of Southeast Europe, one could find the same kind of activity taking place within the cities. In Omsk, Russia, the capital of the White Forces, a group of Anarchists carried out a bank robbery on the night of May 31st, 1919, removing the sum of 400,000 rubles. The secret service made an interesting report of the event and provided the most interesting details, "...the thieves did not take the personal money of the employees, since they were ideological anarchists..." And, of course, the Anarchists assured the employees and witnesses, "the money was taken for a good purpose." [*83] This underground of anti-Bolshevik guerrillas and partisans earned the nickname by official authorities as "Anarcho-Banditism." One of these organizations, "The League of the Red Flower," declared that its purpose was terror againts the Soviet State and Party Officials. Not only did they fight the Communist Government, but they carried out expropriations of wealth that Capitalists had possessed. [*84] The Anarchist, Black Army of Nestor Makhno had established an Anarchist society for millions of people in the Ukraine Free Territory. Their collectivist experiment was brutally crushed by Red, Bolshevik forces, but the Makhnovists kept operating for a time. Jan., 1922, Zaitsev and a group of 70 fighters were crushed; in the same month, in the village of Vozvizhenka, a group of 11 fighters was defeated. Feb., 1922, the Ivanov detachment of bandits was destroyed by the Red Army, a group of 120 people, and in Poltava and Lonstov, another detachment of 200 people surrendered. Mar., 1922, a group of 134 Makhnovist fighters was destroyed while operating underground; and in May, the Boiko insurgent detachment was defeated by the Soviets. These were all celebrated by Pravda in tones such as: "Red Army Defeats Bandits." [*85] By 1925, it was no longer popular to talk about Anarchist banditry, and so the term "Kulak Banditry" was invented, in order to deprive the people of any sympathy with the crushed rebels. In Jan., 1925, Red forces still had not eliminated all the connections, bases, and armaments of anti-Soviet forces, and began organizing serious drives to completely exterminate these groups. The state went so far as to create a Permanent Council on the Struggle Against Banditry of the Soviet of People's Commisars in late 1922. [*86] In the early 1930's, Anarchists in Kharkov, Ukraine, began to get organized in resistance to the brutal, state-enforced collectivization happening on the farms. Yet, they had a problem: "...money was needed in order to create an underground printing shop, and they didn't have any." One of the Anarchists suggested "undertaking a robbery ('expropriation')," but others, more conservative and aligned with other political interests in Russia, were able to discourage the group, saying that they could make the money they needed by "selling pottery" from an old commune on the outskirts of Kharkov. What happened to this particular group, it is impossible to say, but little is heard of them afterwards. [*87] During the 1920's, the anti-Bolsheviks in the West were crushed by the Bolsheviks in Moscow. Who helped them? They had the aid of certain forces in Eastern Russia: the Muslim population. As soon as the Anarchists and the Ultra-Left was eliminated by the late 1930's, the Soviet government disavowed any rights of religious freedom, and began dismissing all Muslim personnel. The Chief of Militia of Kokand was arrested, but he escaped very easily, probably with the aid of the local population, and he quickly "began to organize raids against Russian settlements and Red Army attachments." Before long, the Soviet government had begun a propaganda campaign, smearing these fighters as "brigands" ("Basmachi"), when the word they had used to refer to each other was freemen. [*88] In the Caucasus and other regions with a great amount of Muslims, the tradition of the tariqat was revived: these were secret societies of workers focusing on a particular trade and being led by a devotional master, a sheikh. Within these societies, they practised education, marriage, burial, and other rituals prohibited by the state. In some areas, the tariqat was eliminated by the brute force of the military. In others, the reaction to the state's brute force was to make the entire population receive its religious services at these underground societies: much of their religious donations found its way into purchasing arms and weapons for the Basmachi. [*89] The Soviet state began by killing Anarchists to protect the Liberals, then by killing Liberals to protect Conservatives, then by killing Conservatives because nobody else remained. This is a record of fact: the resistance to Mahknovist and Anarchist forces in the beginning, the elimination of an independent intelligentsia, and the elimination of Nationalist and religious-based causes, like the Muslim Tariqats. What followed next in Russian history was: The Period of Prisons. In the Bolshevik Prison System, the government enacted Article 58: the separation of imprisoned people who hurt society and imprisoned people who hurt the Soviet government. To some Westerners, this distinction may seem odd, as though the government admitted it had political prisoners, but the reasons are much more complicated, such as prison officials being worried about imprisoning someone who might be popular in the next election round, and wanting to be freed of the guilt of their actions -- the way firing squads often have one rifle with a blank bullet, so that any participant might imagine themselves as innocent. Yet this had a completely unexpected result on the prisoners, according to Solzhenistsyn, the man who invented with the word Gulag after having experienced notorious prison conditions: "...they [the criminal prisoners] realized that they were not spiritual paupers, that they had a nobler conception of what life should be than their jailers, than their betrayers, than the theorists who tried to explain why they must rot in camps." [*90] Such camps were a cultural, melting pot. The Ukrainian Anarchist, who had studied with freedom-loving, Atheist students in Paris, was met face-to-face with the East-Russian Muslims who traveled with Qur'an-loving, Islamic pilgrims to Mecca. They looked into each others' eyes and said, "We are all article 58's. " But, they were also all inmates ("zek", in Russian). Zek's with criminal sentences exceeding the probable lifetime of the Soviet Empire engaged in regular murder of the stukachi (the "informers"), because they could only receive an increased sentence. Sometimes these prisoners received aid or communication from groups working for their nationality, or for their religion, or for their political beliefs, often with some helping hand of an ex-prisoner still living in a town near the prison. [*91] When it came time to pick who is and is not an "Article 58", many remained behind in ordinary, regime camps with their political ideals still boiling. In a number of events, groups of criminals forged underground societies called Blatnyes (best English translation: "Authoritative Thieves"), known for their prison tattoos, and these refused to cooperate with the local police or prison authorities at all. The other half of these camps served the political authorities endlessly, and had earned the name Suki (best English translation: "bitches"). Warfare regularly broke out between these groups, sometimes resulting in hundreds of deaths. In the end, it was the article 58's who "had less to lose, something to fight for and a greater sense of solidarity," but everywhere, there was rebellion in these camps. [*92] In 1948, a secret society of anti-Nazi, Russian officers disarmed or killed their guards at a prison near Vorkuta, managed to liberate a nearby camp, and marched on Vorkuta, before being driven back by paratroopers and bombers. A strike among the forced workers at Ekibastuz, Kazakhstan, in 1952, similarly caused stirrings throughout the camps. And in May, 1954, also in Kazakhstan, a prisoner aimlessly walked into a forbidden zone of the prison, and was executed on sight -- this caused rioting in the forced labor camps at Norilks and Kengir. These criminal societies had generally all the same kind of demands: "a re-examination of all sentences; better rations; a shorter working day; the right to frequent correspondence and visits; elimination of numbers from prison clothes;...no reprisals..." Describing one particular revolt of the criminal society, we can read... "At that moment some Ukrainian women, dressed in embroidered blouses, which back at home they probably used to wear to church, linked arms and, holding their heads high, walked towards the tanks. We all thought the tanks would halt before the serried ranks of these defenceless women. But no, they only accelerated. Carrying out Moscow's orders, they drove straight over the live bodies." [*93] By the end of the 1950's, these criminal societies had achieved most of what they had requested of the political authorities. In the 1960's and 1970's, criminal societies of a secret nature continued to thrive in Soviet society. The black market is one known area, where commodities were available from workers who reported items lost or damaged in transport, or simply by stealing them. Some of these same workers had such a mutual sense of solidarity, that they often used their "state-owned industry" as a front for a black market operation that had could use the official, state-controlled markets. [*94] And the Tariqats of the Muslim brotherhoods continued to be active. In some parts of Russia, like the Caucasus, one Soviet report suggests half the population belong to these secret, criminal societies. [*95] The Soviet authorities were not the only ones to distinguish prisoners between course, common criminals and sophisticated, political prisoners. We already know of the Italian example. The Nazis in Lithuania, quite within the Slavic orbit of Russian influence, had adopted a similar system when they built their concentration camps. One Nazi officer, in 1943, gives the following explanation for the distinction... "The non-politicals, we keep them in here because they would destroy society. But you, the politicals, we keep you in here because society would destroy you." [*96]

China

Russia is between the West and the East, between those inspired by Rousseau and those empassioned by Muhammed. If you went north, you would drown in icy waters, but if you go south, you may just find some of the same elements of Illegalism and the Criminal Society -- here, in China. In the Chinese novel the Water's Edge ("Shui Hu Chuan "), one can find the story of 108 fugitives who consider themselves to be on the run from "unjust officials." This book had been written by the year 1300 CE, making it relatively late in Chinese history. But by this time, people had understood that "banditry and peasant violence are closely linked to the over-all state of the society." When the government is "unable to manage the affairs of the state," then it is natural that "people seek alternative solutions to the prevalent disorder." [*97] This attitude can be found in most thinking throughout all Chinese history. In the Zhuangzi, the Chinese Taoist text dated to sometime between 400 BCE and 200 BCE, a famous robber argues with Confucius that he has more virtue than the governments that Confucius supports. The criminal underworld is "only the inevitable horrible flip side of the Confucian attempt to impose a supposed moral order on a world perfectly capable of ordering itself." [*98] Bao Jingyan, the Taoist philosopher living some 600 to 800 years later, wrote of these criminal societies that.... ...all the revolutionaries, the oppressed, the sufferers, victims of the existing social organization, whose hearts are naturally filled with hatred and a desire for vengeance, should bear in mind that the kings, the oppressors, exploiters of all kinds, are as guilty as the criminals who have emerged from the masses.... it will not be surprising if the rebellious people kill a great many of them at first. This will be a misfortune, as unavoidable as the ravages caused by a sudden tempest, and as quickly over... [*99] Throughout the Chinese Ming Empire in the 1600's, many cities made makeshift regimes against the government, "pacified areas broke out into revolt a second time" and "unpacified areas aspired to forms of local autonomy." There were many classes who influenced society among these times, from the wealthy and powerful to the literary and educated, but the following grouping had a particular strong influence... ...local sea and land militia, freelance military experts, armed guards from private estates, peasant self-defense corps, martial monks, underground gangs, secret societies, tenant and 'slave' insurrectionary forces, and pirate and bandit groups. [*100] In the early 1600's, the Ming empire was trying to subdue the subject populations of Mongolia and Manchuria (then "Jurchen"). They drafted so many soldiers that nobody was left to defend the cities and "gangs of roving 'bandits' .... were snowballing into rebellious armies..." These created permanent, criminal societies, and when the government raised an army to destroy them, the criminals won without contest, "in part because the imperial forces hastily raised to oppose them often proved no more disciplined -- and rather less fair-minded when it came to sharing their spoils with the oppressed." [*101] Society was forced to a standstill, and the forces at work were: "...intellectual ferment, natural disasters, economic meltdown, industrial unrest, widespread brigandage and piracy, unruly militias..." [*102] But these many of these struggles were against the Chinese empire, ending with crude bloodiness, their downfall only leading the way to new empires. Then things changed when the British authorities landed on the shores of China. In the capital of Guangzhou, British forces established an armistice with the emperor in 1839, while their forces were let loose into the countryside, in a wave of rape, torture, and inhuman violence. Nobody was willing to fire a shot against this state-sanctioned monster -- except for the criminal societies. British rape visited the town of Sanyuanli, where peasants and criminals, "amid heavy rainstroms, they engaged and briefly repelled a force of Indo-British infantry, inflicting minor casualties." It was no amazing victory, but like Durruti in Cuba, or Bonnot in France, or Solzhenitsyn in Russia, or Robin Hood in England -- the story expanded.... "...Sanyuanli stimulated a bewildering upsurge of other irregular bands and secret societies operating independently of the Qing authorities and often in defiance of them." [*103] Following the Opium War with the British and the miserable defeat of the Qing dynasty, the economy sunk to the bottom of the sea with the future of the average Chinese citizen with it. Red Turban armies and Muslims separatists from Guangdong and Yunnan fought against imperial authorities. Peasant bands, known as the "Nian" , fought against imperial interests all thorughout Anhui and Jiangsu. The secret societies of China, known as the Triads, took over entire cities, like Xiamen and Shanghai -- where, according to modern historians, "they behaved quite responsibly." [*104] In the words of one historian, by the mid 1850's, in China, "secret societies mobilised among the rural masses; ethnic minorities rebelled in the hills; pirates infested the coast." [*105] All of these secret societies were minor when contrasted to the wider Chinese society. This is true of them all, except one in particular: the Taipings. This group represents an interesting mixture of Western ideas: Christianity, Communism (equality of property), Feminism (equality of genders), and Cultural Diversity (equality of ethnicities). With the aid of Great Britain, the United States, and other western powers, the Empire of China was able to squash this rebellion; 20 to 40 million lives were extinguished. More human beings died for belonging to the criminal society of the Taipings, than all the human beings who died during the entirety of World War 1. [*106] The Qing dynasty did not remain popular for very long after the Taiping Rebellion, and soon, Sun Yat Sen began organizing for a coup against the monarchy, in favor of an elective government. He spent his life mobilising and supplying arms to all sorts of illegal and criminal elements in the world: "the Triad societies, labour organisations, agrarian movements, trade boycotts, disaffected army units..." [*107] With the success of the Republican Revolution in 1911, these "secret, criminal societies" were literally legalized, and allowed to operate openly without fear of arrest. Some remained devoted to their lifestyle as "social bandits," some even joined the Communist Party, but unfortunately, the majority of these criminals were co-opted by the Kuomingtang government -- they traded in their ideals for a steady paycheck and a regular set of orders to violently break up any labor organization. [*108] In the port cities in our modern era, workers began to resist the modern, Communist State in China in a number of ways. Some "took the form of anarchist labor syndicates modeled after the French variety," others formed societies based on "various leftist or national projects." These societies were tied by "simple anti-foreign sentiment" as much as they were tied to "loftier universalist goals." The common details of these groups: they were secret, they were armed, and they were illegal. Some of the outstanding details of some groups: they were staffed by martial artist fighters, they planned mass riots, and they took part in assassinations of industrialists and the complicit government officials. [*109] We still find this attitude in very modern China, so modern that I can feel the water from our conversation's vapors on my hands. In some Chinese factories, bosses "would beat workers, some hitting so hard that they broke people's arms and legs." All this was to appease the Chinese, Communist State, who was trying to get funding from Capitalists overseas. A few bankers and accountants in Beijing have the power to force this situation on the people. But, they have no power to control how the people react. Such managers, as soon as they left the factory, were attacked and beaten "by gangsters and vagrants." [*110] From the ground, looking upwards, I would describe these organizations in China as Anarchist, popular with the people, and ultimately criminal. But in the official presses, looking downards, you will be able to read the words of the Communist Party mouthpiece, Chen Duxiu, who suggests that these criminal societies are nothing by "nihilists" (those who believe in nothing). When asked for clarification, Chen responded, "They are low grade anarchists!" [*111] It is likely that they were not actual Anarchists, but socially-aware bandits, like the majority described so far. In the list of professions he provided for this group, he added "frauds", but, like any philosophical conversation, we Anarchist criminals look back at the state and say, "Who is more fraudulent than those who use force to establish consensus?"

Asia

Shanghai or Shenzen, Beijing or Taipei, Hong Kong or Guangzhu. If you put me between any two Chinese cities, it is possible to triangulate the direction and strength of Asian culture, in terms of influencing others and being influenced by others, throughout all of the Pacific. China can be found in every part of Asia -- but the reverse is equally true, and all of Asia can be found in China. In Indonesia, so-called "modern history" begins with written history, since much of the ancient culture is preserved only in native, non-written format. In the 1700's, the state-sanctioned Dutch East India Company (VOK) proceeded on a campaign of genocide, slavery, and inhuman treatment in Indonesia that would compare well with the savage techniques of Nazi internment. When not desired, entire islands were exposed to systematic genocide because "some other European power may claim you." [*112] In Jambi, the heart of the Indonesian island Sumatra, the VOC made a number of extreme slave-raiding attempts on the population, as well as a blockade of the port. The resistance was so unbroken that the port survived the siege, defeated the VOC, and was a source of pirates targeting the VOC ships into the 1800's. [*113] The criminal society was not just in the ancient world, but the modern, too. Sukarno, the democratic symbol of the nation, was imprisoned, and his followers oppressed, by the deeply Authoritarian Suharto, who eventually was responsible for tens of millions of deaths. One of those who resisted Suharto was Colonel Imam Sjafei, a boss of the Jakarta underworld who organized his thugs to fight anti-KAMI ("anti-Communist") para-military groups of the government. [*114] In Australia, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) were an active part of the anti-state, anti-capitalist resistance in Asia. J.B. King, the Australian IWW member, was arrested for being the chemist in a counterfeiting scheme, and the profits of this scheme were used to fund arson against prominent state targets. Tom Barker, one of the lead organizers in the Australian IWW, recalled in his memoirs that "we had many little groups amongst us who were doing various things, and those things were deadly secret and they kept them to themselves." [*115] Here, the recruiting poster for the IWW will sound familiar... ...[looking for] recruits, male or female, for the Industrial Workers of the World. Must be determined, unafraid of gaol or death, and unscrupulous. Apply to the nearest IWW recruiting office. [*116] In 1859, the French Imperial forces took Saigon in Vietnam, and afterwards, they began moving northward in a series of aggressive, territorial seizures. But they found fierce resistance, including the Muslim underground bands of Red Turbans from China, republican or nationalist Chinese troops gone into hiding, Communist cells, and all sorts of criminal societies. [*117] Ho Chi Minh, the Communist leader who would lead the liberation against the French, had during his lifetime "adopted more than fifty assumed names." [*118] The French were also directly hindered by "eclectlic politico-religious" sects, such as the Cao Dai, the Hoa Hao, the Đại Việt's (Nationalist resistance group), and probably a number of Chinese counterparts, such as the Green Gang. [*119] In Japan, Yukio Mishima penned the book the Temple of the Golden Pavilion, in which he depicts a Buddhist monk, who is humble and obedient, but also abused and bullied for uncontrollable stuttering. He spends hours praying for the Allied forces to bomb his temple, and when they fail, in a fit of rage and disappointment, he grabs a gasoline canister and does the job himself. The author of this tale, Mishima, eventually committed suicide after a failed Samurai coup, but his perception of the criminal society also became part of Japan's perception of it. In Australia in the 1980's, three computer hackers, Phoenix, Electron, and Nom, went on an endless spree of piracy, theft, and sabotage. Their main target was not money, but information and knowledge. When they had acquired enough of this, they hacked into NASA's computers during the government's controversial use of nuclear and plutonium power, and spread a virus that shut down the entire NASA network. They called themselves the Realm , and their computer virus was responsive, took counter-measures, repeatedly screamed anti-war slogans, and could've been a contestant for self-aware, computing programs. When the police raided the group, the most sophisticated technology they used was: turning off the lights. [*120] Phoenix was quoted by police as once saying: "Yeah, they're gonna really want me bad. This is fun!" [*121]

Middle East

Between Jakarta and Saigon, between Sydney and Kyoto, between the stormy seas and the calm rivers, the stark, mountain peaks and the gloomy, moonlit nights; if you look west from here and keep moving, you will find yourself in a place called the Middle East. The Muslim priest Mazdak, whose followers were known as Mazdakites in the 5th Century BCE, may be interpreted as a "Proto-Socialist," with ideas far beyond what traditional thinkers considered acceptable. [*122] When his group were oppressed, they were driven underground, and turned into secret sects; when they grew strong enough, they renamed themselves the Khurramites ("Khorrām-Dīnān" ). The primary organizer of this criminal society, Khidash, continued to struggle for the Socialist cause, always making trouble for the local governors. [*123] In Baghdad, Iraq, around the year 800, the poverty of the Islamic society became so bad that groups of outcasts ("sasiyan" ) and beggars banded together to form guilds for their mutual protection, even if these societies were illegal. [*124] By the year 1000 BCE, Sufi fraternities and craft worker guilds began to merge, taking on elements of mysticism. The "Brothers" ("akih" ), also known as the "Knights" ("futuwa" ), were one particular "underground fraternity" who were known for presenting "a noble and fairly organized opposition, based on Islamic precepts, to tyrants and social injustice." [*125] By the year 1800 BCE, a new society arose: those of the Ba'hai faith, who sought race, gender, and class equality, and almost everywhere, they were driven underground into societies where it was a crime to be a member. This was not the last outpouring of Illegalism in this part of the world. When the Kurds were denied independence or autonomy in the Middle East after heavy European involvement in the 1990's, they "carried out ambushes, industrial sabotage, and robberies aimed against the [West-supported] Iranian state..." [*126] Thousands of people died in this struggle, but when it finished, millions had attained their liberty in their own society, without sexism, racism, capitalism, the state, or any form of exploitation. This was the Anarchist experiment of Rojava. Long ago, before the Middle East knew anything at all about Islam, there was a distant group of outcasts who would never be accepted in society: the Bedouins. They drank liquor, snuffed tobacco, smoked opium, puffed on cannabis, and took part of creative, sexual lifestyles; their culture was crime and their power was the ability of movement. They could raid caravans and disappear into the sandy air. Even when Islam was conquering Spain, Italy, Mongolia, China, and Istanbul, they still had not conquered the Bedouins. While the law-obeying world was easily destroyed, the criminal society survived and grew. [*127]

The Americas

If you're standing somewhere between Istanbul and Baghdad, somewhere between those palaces made of stone and those fortresses made of rock, and you look to the west and follow that direction, there is only one place you will be taken: the Americas. Quilombo: this word is used to describe communities of runaway slaves who had merged together, formed their own society, and, in its most developed state, proceeded to carry out raids of liberation against their former slavers. It was first used to describe societies in Brazil in the 1600's (sometimes called "Mocambo" , for "hideout"), but then the term spread everywhere, encompassing millions of people: the Caribbean islands, Central America, throughout the swamps of the United States, and everywhere in Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia, and French-colonized parts of South America. The people who live in these communities and their descendents, numbering in the tens of millions today, are known as "Maroons" or "Quilombolas" . The definition of the Maroon in its original Spanish is: "Dwelling on peaks." [*128] In so-called New Spain, those regions of the Americas discovered by this Imperializing power, there was the legal world of slavery, and the illegal world of "smugglers, cattle-rustlers, bandits, the buyers and sellers of clandestine produce." To give a full picture... In such a society, even the transactions of everyday life could smack of illegality; yet such illegality was the stuff of which this social order was made. Illicit transactions demanded their agents; the army of the disinherited, deprived of alternative sources of employment, provided these agents. Thus a tide of illegality and disorder seemed ever ready to swallow up the precariously defended islands of legality and privilige. [*129] In Colombia in the early 1900's, peasants worked within extensive networks to smuggle goods without paying taxes, including liquor, tobacco, medicine, and even armaments. These networks survived repressive measures because of "community institutions, cohesion, and communication." [*130] In Mexico around this time, leaders like Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata had used traditional, bandit tactics of hit-and-run attacks against state and military forces. [*131] While Zapata fought a corrupt state, Pancho Villa, like Salvatore Guiliano, was eventually co-opted by the state, following orders to detain local Anarchists before himself being killed by a mysterious assassin. By the 1950's in highland Peru, intense class warfare raged on between the poor peasants and the dominating landlords. Those villagers who fought back and became Illegalists called themselves "'the foxes' and, in talking of their tactics, they endlessly contrast the cunning of the fox with the strutting by empty courage of the rooster." [*132] In Uruguay, in the 1960's, El Santa Romero carried out a number of bank robberies with his comrades, also members of the Anarchist Federation of Uruguay (the "FAU"); one day, the police laid an ambush for him, and he was trapped, but, unlike typical standoffs with the police in South America, "at no time did it occur to him to take a hostage: such things were unthinkable to him." While being interrogated and tortured, he never revealed the identities of anyone within his criminal society. [*133] The armed branch of the FAU was known as "OPR-33," and it was operating in a Dictatorship-controlled nation. Their activities are numerous: the stealing of Nationalist memoribilia from museums, the kidnapping of Pepsi and other foreign CEO's, and, of course, bank robberies. [*134] The funds were used for all sorts of purposes: propaganda, "strikes, factory take-overs, etc." [*135] One of the kidnapped CEO's, Molaguero, was particularly hated in Uruguay: he used his privilege as CEO to sexually assault and grope female workers. When the laborers formed a union and camped outside of the factory, police and the army were brought in and they proceeded to burn down the camp. Molaguero was kidnapped, and only handed over after OPR-33 made a list of demands to the company that went like this...

The Argentinian novel Burnt Money by Ricardo Piglia depicts the events of a 1965 bank robbery in Buenos Aires, held up by two outcasted gay lovers from society; when tracked down by police, they refuse to turn over the funds to the state, setting it into a blaze, resisting to the last bullet, and being found dead, holding hands. [*137] In more modern times, we find the same type of social bandits in Brazil. Here, peasants and the working class engage in saques ("lootings") during bad times in the economy. This is often a planned activity, with a group looting "from a store, warehouse or truck, and then distributing them among those who do not have enough." But even some members of the established society supported this behavior. Miguel Arraes, governor of Pernambuco, Brazil, said "to confuse saques with assault or robberty is to treat a very serious social issue with violence," and Catholic archbishop João Pessoa, said those who steal "in order to survive do not sin." Naturally, the president of Brazil was very critical of both of these voices, but it was not enough to stop the activity. [*138]

We Are All Criminals

"What secret societies do you belong to?" the police officer asked me. I took a long drag on the cigarrete I had been offered, and in between puffs of creative clouds and atmospheric energy, I responded, "All of them." There are many names for us: Illegalists (France), Expropriators (Spain), Klephts (Greece), Haiduks (Serbia), Haiduts (Bulgaria), Proletarian Shoppers (Italy), Robin Hoods (England), Br'er Rabbits (USA), Article 58's (Russia), Basmachi (Caucasus), Tariqat siblings (Kazakhstan), Nian (China), Red Turbans (Uighur), Mazdakites (Persia), Sasiyan (Middle East), and Quilombolas (South America). What is the definition of an Illegalist or Criminal Society? I give it this one: those who steal from the exploiters, and in so doing, are able to materially or culturally enrich the exploited. These lawbreakers belong to this great, criminal society . Organized crime, like the Sicilian mafia or the Russian mafia, is as far away from our criminal society as all the judges and politicians of the world. One thing the casual reader will notice about this work is: Why is it that these particular countries or continents happen to be featured? Where is Africa in this work? What happened to the Pacific Islands and pre-Colombus Americas ? Why did these places develop no criminal societies? Why did we not hear from them? The answer is: these pre-industrial societies had only a few types of wealth, which were often freely available to all, and they possessed nothing like money. What is the point in robbery or smuggling or counterfeiting, when the thing being obtained is freely available to all anyway? The mere concept of crime does not exist in these worlds. There is a minor tone of sadness or lostness in this answer. Criminal societies did not exist until there were empires and conquerers and imperialists and slavery -- the word "empire" is synonymous with "Spain", "China", "Russia", etc... One day, we will be rid of all of these things; and, so too, the criminal society will cease to exist, for it shall have no purpose. To belong to the Criminal Society today, to be an Illegalist in our era, is to exist at a very special, very short period in all of human history. But because of us, perhaps that future will come a little bit quicker -- even if nobody knows about it. The present is the golden age of criminal societies. In the ancient era, humanity was too poor to fight and struggle with each other over scraps. In the futura era, humanity will be too rich to bother with fighting and struggling. We, who live in the between-era, we are the only ones who may yet be completely free in this purely individualistic sense -- if only we are criminals. Punkerslut, Resources *1. "Wrong Steps: Errors in the Spanish Revolution," by Juan Garcia Oliver, Kate Sharpley Library, 2000, Section 1: Juan Garcia Oliver -- Introduction, Page 1.

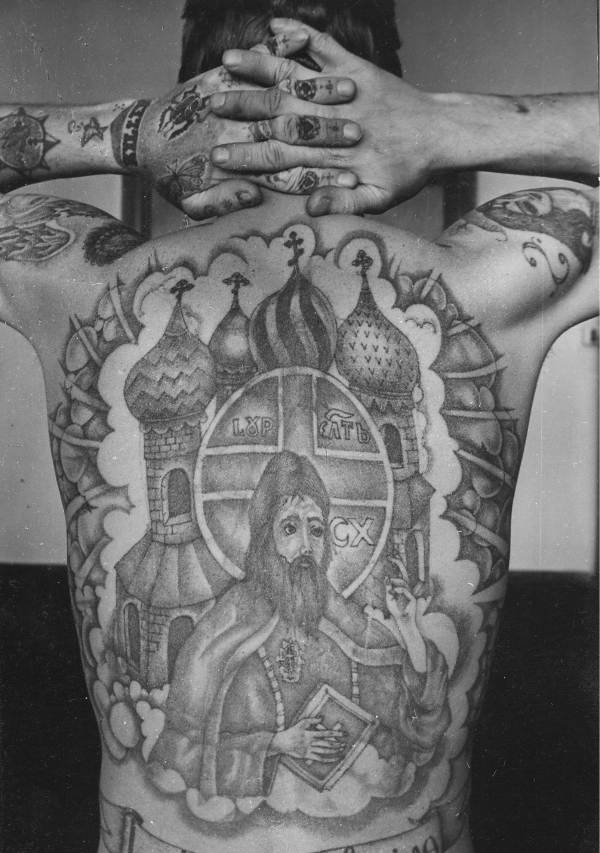

|